Winter

My mother likes the family to start the New Year together. Ideally, we’d all be at church, but she pities the sinful and lets us have a party at our house instead. We invite the family over. We cook all of my favorite appetizers—Pigs in a Blanket, Spanakopita, quiche—and hang streamers everywhere. We place bowls of nuts on the tabletops, next to conflictingly scented candles (all supposed to bring good fortune). My father always insisted on serving rice pudding for dessert; he thought it was good luck to start the New Year with it. I usually ate so much food before midnight that the thought of dessert was nauseating. I never ate the rice pudding.

New Year’s Eve in 2015 was the first year my family did not spend it together. One brother was with his girlfriend one place; the other was with his girlfriend another; my parents were at church; and I was at an apartment party in Brooklyn, stultifying a stranger for not knowing who Adele was.

I told everyone my New Year’s resolution was to read thirty books.

I started by reading Fates and Furies, in which Lauren Groff shows through both perspectives of a marriage that relationships are mythological—so much of it is in our head. Regardless of how much time we spend with a person, or how intimate we believe to be, we only know what they show. There’s deceit in the concealment, and the pretense.

The New Year began and I wasn’t a new person. I was still living at home, which I resented, not because I disliked living with my family, but because it set me apart from my friends—both physically and abstractly. I lived at home, and that meant I wasn’t an “adult.” More frustratingly, that meant I couldn’t hang out with friends at a moment’s whim. Everything in my life was annoyingly structured. I worried about missing out, so in effect over-booked myself to the extent that I was ubiquitous to my friends and the city.

That was really important to me: being available.

I read The Goldfinch in February, when I was running around the city from activity to activity, somewhat in parallel to the book’s portrayal of a tumultuous pilgrimage a young boy, Theo, makes after his mother passes away. One of the most influential characters Theo meets is Boris, the son of an abusive father with whom he instantly forms a connection. Theo and Boris are in each other’s lives for a short period of time before Theo moves away again. They meet again in New York years later, and the loyalty and bond the two once shared is resurrected—in spite of Theo learning that Boris betrayed him years before.

Boris, a boy prone to making brash decisions, makes it apparent that not all deceit is harmful and people can cause harm unintentionally. In contrast, Tartt’s character, Henry, from The Secret History would argue that pain is necessary for a greater good. Henry, unlike Boris, is scholarly and systematic. He is part of a coterie of Classics majors at Hampden College who aim to bring their Ancient Greek studies to life with a Bacchanal gone wrong. The sequence of events that follows is an ongoing attempt to course correct by doing something unspeakable.

I read The Secret History after The Goldfinch, and decided that maybe friendships aren’t what they’re cracked up to be.

Spring

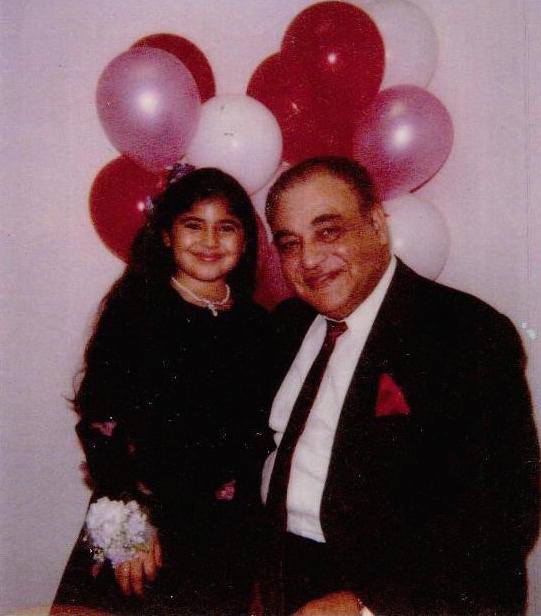

My dad was turning 75 years old, a milestone I would not let go uncelebrated. He didn’t want a party. I wanted a big party. We compromised: I told him we wouldn’t have a party, and then secretly planned a party for him.

He couldn’t believe it. He spent the rest of his life gushing about it, incessantly thanking me, and trying to force money on me to pay me back for what he assumed was money spent well beyond my means.

The weather was warmer, and my priorities had shifted unintentionally. I wanted to spend time in New Jersey, where I could sit outside and feel the sun burn my shoulders. Every night, my dad and I would sit outside until well after sundown, our legs covered in bug bites we chose to itch rather than prevent by sitting inside. We began a tradition of hosting all of our cousins, aunts, and uncles every Sunday. My father learned what “potluck” meant and in turn taught his brothers and sisters the meaning; they all began to bring drinks, desserts, and burgers.

One of my uncles complained every time we invited people over; he thought I was burdening my father with these weekly reunions. He said my time was better spent looking for a husband, someone to take me off of my father’s hands. My father and I laughed this off.

I was reading The Nest in April, an entertaining book about four siblings (the Plumbs) and their quest to get their share of a promised—and highly anticipated—inheritance they amusingly refer to as “the nest.” These brothers and sisters, much like my father and his siblings, are all very different from each other, each filling a unique and specific role in their family. One sibling, Leo Plumb, has an enigmatic and charming personality that drew people closer to him. He’s a troublemaker, and the reason his three siblings are concerned about their expected pots of gold. Leo reminded me of stories about my father when he was younger: reckless, but engaging, and fearlessly bold. I grew up hearing stories about how my dad protected his siblings from bullies and got into trouble for throwing house parties and sneaking out late. My father would have his friends push his car down the street so his mother wouldn’t wake up to the car starting after curfew. His siblings all seemed like goody-two-shoes in comparison.

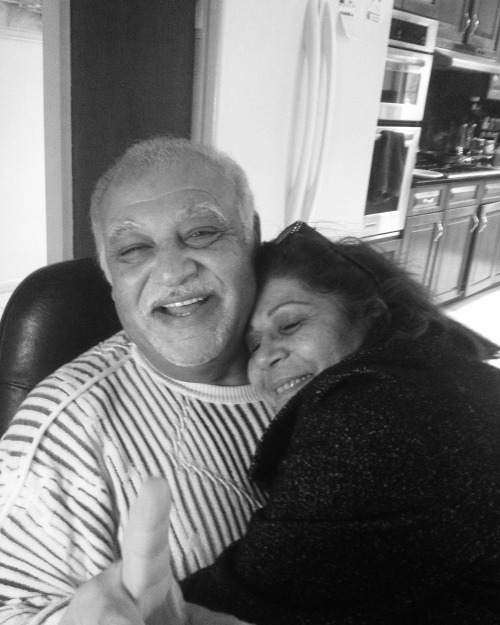

Even with 75 years on him, my father still had the dominating personality I heard so much about as a kid. When he spoke, the room quieted before erupting with laughter. My mom, who always laughed along, would sometimes feign horror at the extent of his jokes, shrieking “Issa!” in between hoots of laughter.

.GIF%EF%B9%96format=100w.gif)

Hanging out with my dad always made me feel relaxed and giddy, like a child. I think that’s because my father, despite his younger bad boy persona, seemed so innocent to me. He demanded respect and probably scared the hell out of a lot of people, but my mom always said he had a heart of gold, the heart of a baby. His lifestyle was much like what Antoine de Saint-Exupéry preaches in The Little Prince, which tells the story about an abandoned pilot who meets a little prince (go figure). The prince recounts his visits to various planets in order to eradicate his loneliness. Along the way, the prince meets a wise fox, who tells him a secret: “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry writes, “All grown-ups were once children... but only few of them remember it.” My father remembered it. Maybe, in some ways, he never grew up.

Summer

Summer is my favorite season—there’s a freedom in the warmth. I like to run in the heat; I like to sleep under the sun; I like to eat outside. I like to watch my skin change colors and my hair get big.

I told my best friend that this summer was going to be the best summer of my life. I made plans from the first weekend of June through Labor Day weekend. I was ready.

My first vacation was a family trip to Long Beach Island for the 4th of July. We spent a week there. One night, we were walking back after dinner and my dad stopped walking. He leaned against a car parked on the street and said he needed to take a break. With a smile on his face, he made a circular gesture with his index finger while whistling low; I laughed, despite my concern. After a moment, he stood up and said he was ok. I thought, This is the first time I’ve ever seen any indication of my father’s age before. I wondered if this was the beginning of a new chapter of my life; if I would begin to watch my parents grow old now. I pushed the thought away. My father and I joked on the rest of the walk back. Everything was ok, everything was normal, time was still on my side.

The following Thursday, I got vague calls from my priest, mom, and oldest brother. I could tell something was wrong, and instinctively called my father to find out what happened. I figured it had to do with my mother or one of my brothers. I didn’t know how serious it was, but didn’t think it was worth me leaving work early after already taking a week off. I went back to my desk and continued working until my cousin called. She was semi-hysterical, talking in circles I couldn’t follow. Finally, something stuck: my father. Something happened. He fell. Working out. I ran out and sat on the hour-long train ride home telling myself nothing happened, clinging onto the hope that no one confirmed anything. I remembered learning in Sunday School that everyone once told Jesus that a girl had died, and he told them she was not dead, but asleep. I read that chapter of the Bible to further verify: I believe this happened.

When I got off the train, my brother, George, met me. He was waiting outside of his car for me. He shook his head once. I told him I didn’t believe it. I got home and saw my dad’s five brothers and sisters with their kids and grandkids in my kitchen. They were all crying. They watched me go downstairs to find him. More family members crying. I told them to leave. I told them he was just sleeping. I told them to get the fuck out. George reminded me that they are his family members, too. I didn’t care. My oldest brother, Joe, was huddled over my father crying. He’d been in that same position for hours from what I could tell.

More people came. No one would leave. I closed my eyes and pretended to sleep. No one could comfort me, and I didn’t want to talk. I wanted my father. I would trade any of their lives for his.

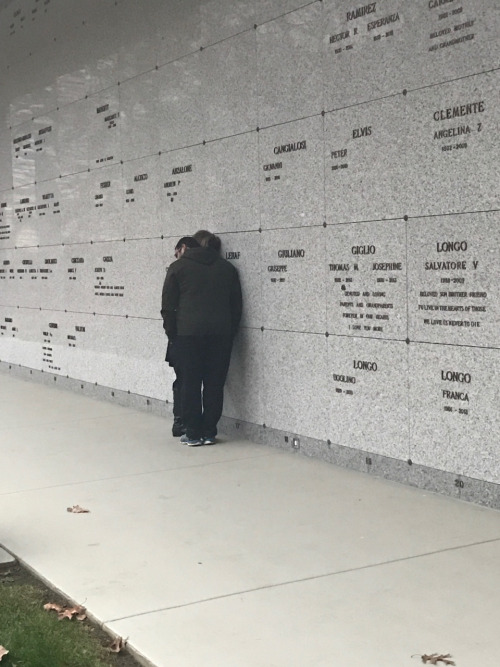

My heart exploded. It exploded when I saw my father’s body. When I held his hand and it felt cold. It burst when they closed the casket and carried it out of the church we had been going to all my life. It crumbled when they carried the casket into his grave and sealed it shut. Just like that: It was over.

.jpg)

A few weeks before, I read A Little Life, a book that spans many years and heartbreaks and had me question why bad things happen, and keep happening, and don’t stop happening. The book follows four friends from college throughout adulthood. While each friend has an internal struggle of some sort—accepting one’s sexuality, drug abuse, defining and achieving and finding content in one’s idea of success—the story is framed around one boy in particular: Jude. Jude seems doomed from the start; he has a haunting past and although he beats many odds, he has trouble moving forward. Jude’s life story—everyone’s life—is merciless. I realized I was tired of searching for hidden meanings, for the reason why things happened. Things happened. No purpose to the cause and effect. People told me, But you’re such a good person, it’s so unfair. Fools. Pain doesn’t discriminate.

Fall

I watched the leaves fall on the lawn my father was no longer maintaining. I used to tell friends to compliment his yard work, that it would make him happy. When they did, he would beam, lifting a tree branch over his head the way John Cusack raised the stereo above his.

I stopped going out. I didn’t really care, I no longer felt FOMO; I felt bound to the groups of friends who came to the wake, funeral, and consistently checked in afterwards. I felt grateful for and secure in these friendships. I knew that even in my absence, these friendships existed, were real, and remained sources of light in a life that turned dark.

I wanted to stay home, to make sure my mom had company. I lost my best friend, but she lost the foundation of her life. She lost her counterpart, the voice in her head, the reason to get up in the morning. My father took care of my mother; he drove her to the hair and nail salon, waiting at his sister’s until someone called to say she was ready to be picked up; he took her to the doctor appointments she needed for the pain in her hands and back and shoulder; he vowed to take care of her, and he kept that vow until the day he left.

.jpg)

My mom needed me at home with her, and as much as the house haunted me, I didn’t want to leave it.

My mom’s sister came from Dubai halfway through the season. It was a nice shift. My mother, who had been on a self-inflicted house arrest for months, now began to leave the house—not for herself, but for her sister. It was her sister’s first time in America in twenty years, and my mother put her grief aside to host. It was nice being able to ask for a table for five again.

My friend who lost his mom a few years back mailed me Living When a Loved One Has Died. It was written in short verses, ideal for my tired mind’s attention span. It told me that “anguish, like ecstasy, is not forever." I woke up every day, and the world was still moving. I was mad at friends, family, work, at every indication that life was going on. Everything should have stopped and paid their respects. A memo should have been released declaring the world over.

I couldn’t pause the world. I couldn’t fight time. I had to think about other things again. I had to remember what I loved about living: people, music, memes, sprinkles, books, people. I read What the Living Do: Poems by Marie Howe. She writes:

“We want whoever to call or not call, a letter, a kiss—we want more and more and then more of it.

But there are moments, walking, when I catch a glimpse of myself in the window glass, say, the window of the corner video store, and I’m gripped by a cherishing so deep

for my own blowing hair, chapped face, and unbuttoned coat that I’m speechless: I am living. I remember you.”

I wanted, want, will always want more. My fear of forgetting my father paralyzes me; how much could memory savor? I have shirts from my father that I won’t wash, hoping they’ll always carry his scent. I look at pictures of him and think to myself, “Is this real? Did this really happen?” Sometimes I can’t tell if I am questioning whether he was alive and mine, or that he’s gone.

I continued to look for closure in words from people who didn’t know me. I paused Zadie Smith’s Swing Time to read my 31st and last book of the year: C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed. Lewis documents his mourning period after his wife, H, passes away, as he comes to terms with theodicy. He opens the book (which was handwritten in four personal notebooks) by comparing the feeling of grief to fear. “The sensation is like being afraid,” he writes. I found that grieving is universal: we all hurt. No one can escape death. Everyone will have to deal with it at some point. I also found that grieving is personal: no one understands. If they’ve lost or when they lose, they won’t be able to comprehend my feelings, memories, or dreams; these are my own and no one else’s. My misery is my own. So is my hope.

On Christmas morning, I sat with a friend and talked to him about my father. He broke up with his girlfriend and told me how he thinks, She was with me when Issa died. And it’s true, she stood beside him and his mom at my father’s wake. She waited with him in line to hug me. She sent her condolences to both him and me.

I told him, "I am 24. What if I live to 75 like my father? This is such a short period of my life for me to have had him."

He said, "Yeah. It is short."

I asked, "But I had him during my developmental years—so that means his significance on my life will never lessen, right?"

He reassured me, "Your brain stops growing at 24, so you had him during the years that shaped you most."

I looked at my phone and found a message from a friend: his father passed away.

I kept re-reading the message, thinking it was wrong. Was he talking about my father still? No. He wasn’t. His father passed away. He didn’t know what to do. He just wanted to let me know.

I ended the year in my friend’s hometown at his father’s funeral. I recognized a mutual friend’s dress from my father’s funeral. She said she probably wouldn’t wear it for any other occasion now. I asked another friend what it was like for them to be doing this all over again. He said it was awful, especially seeing someone you care about hurting. A friend from a nearby town had his father drive us to the funeral. His father asked us in the car, "Are you guys going to come to my funeral when I go?"

A crowd surrounded the family as they lowered a father and husband into the ground. My friend threw dirt atop his father’s casket. Just like that: it was over.

Natalia is an editor of Things Created By People. Find more of her work on her website.