When one thinks of the Weimar Republic, images of cabaret, women in short haircuts and pencil skirts come to mind. The New Woman was also represented in these images and is almost synonymous with the era itself. While many artists of the Weimar Republic criticized and challenged the political and cultural assumptions of the Weimar Republic, very few called the idea of the New Woman into question. Hannah Höch was a German artist active during the Weimar Republic, whose photomontages critique and question the role of the New Woman in German society. Combing through the rapidly expanding popular print culture in German, Höch’s photomontages and other projects during the Weimar Republic simultaneously challenge German culture and society’s perception of women.

After the armistice ended the First World War, it became easier for artists to travel around the continent. One of those artists, Richard Huelsenbeck, returned to Berlin from Zürich and brought with him the spirit of Dada. The Zurich Dadaists’ interest in Cubism and Futurism, the spirit of confrontation and experimentation, and their enthusiasm for performance and spectacle found a new audience in the turbulent German capital. Calling themselves Club Dada, rising and later famous artists—such as George Grosz, John Heartfield, Wieland Herzfelde, Johannes Baader, and Raoul Hausmann—collaborated on publications and exhibitions.

These artists, however, lived in a more politically radical environment than the sleepy town of Zürich. The armistice was only the beginning of a long and arduous transition of power within Germany. Kaiser Wilhem II had abdicated the throne and fled the capital shortly before the armistice was signed and the much of the Navy had already mutinied. Major cities across the nation, including Berlin, were beginning to be controlled by councils of mutinying sailors and soldiers. The workers and sailors council in Berlin was one of the strongest, and it was led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg, co-founders of the German Communist Party (KPD).

Club Dada was mostly comprised of Communist party members or artists with communist sympathies. Höch was part of the latter group. Regardless, all members felt their hopes shattered and already betrayed by the new republic. Höch herself described a “feeling of alienation” as a driving force for the political and acerbic art that the Club Dada produced between 1917 and 1922.1 These exhibitions culminated in the 1920 exhibit titled, “The First International Dada Fair” (“Die Erste Internationale Dada-Messe”) from June 30th to August 25th of that year. They constructed sculptures out of found materials and propaganda posters with nonsense slogans. Most importantly, they experimented with the newly invented medium called “photomontage.”

Nearly every member of Club Dada claimed to have invented photomontage, but Richard Huelsenbeck, the unofficial historian of the Dadaists, supports Hannah Höch’s description of how she and Raoul Hausmann invented the practice.2 While on a vacation with Hausmann in the Baltic, they noticed many of the mothers and widows of the town had small, postcard-sized paintings of men in uniform. Where the painted head should have been, however, was cut out and replaced with a photograph of a son or husband pasted onto the paper. This mixing of mediums fascinated the pair, who began experimenting while still on their vacation.

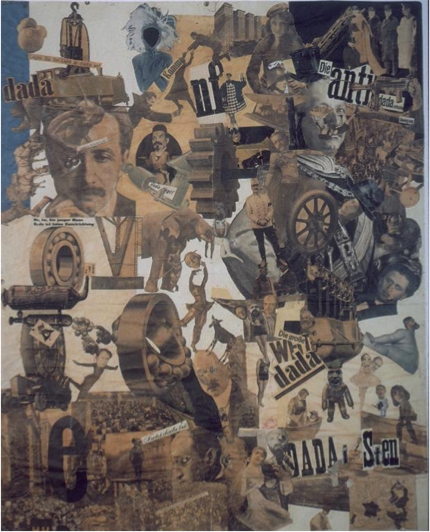

The major themes and characteristics of Hannah Höch’s photomontage work were established early in her career during the Dada years. This is not to say that she remained trapped in a certain style or that she did not develop after the Dadaists disbanded in 1922, but rather that her Dada works establish common themes such as androgyny, satire, and popular mass-media imagery that continue to play a significant role in understanding her oeuvre throughout the decades following. Höch’s most famous work, Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany) (1919) (Figure 1), was exhibited at First International Dada Fair in 1920 and one of the best examples of Höch’s early mastery of the photomontage medium. The salacious and long title propagates the agenda of the photomontage - to use the sharp weapon of montage and Dada critique to attack the fat, bourgeois gut of the new Weimar Republic. Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser maps out the “Dada” and “Anti-Dada” forces in the new Weimar Republic in a swirling circular diorama. The “Anti-Dada” elements in the top right corner of the photomontage are surrounded by the “Dada” on the bottom right below them.

Figure 1. Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany), 1919-1920, photomontage, Nationalgalerie Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz Berlin.

The abundance of newspaper clippings and photographs from which Hannah Höch was able to choose during the Weimar Republic reflected a cultural shift in journalism. After World War I, Germany experienced a publishing boom. Advances in technology made cameras lighter and photographs easier to develop. The largest of the post-war publishers was Ullstein Verlag, who had the widest circulated and most influential newsmagazine, Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung (BIZ). By 1930, BIZ had a national circulation within Germany of 1.85 million copies, with its nearest competitor’s highest circulation hovering around less than a million copies.3 The popularity of the BIZ was due mostly to the abundance of photographs in its pages. With the technology to mass produce photographs, the whole German population consumed them in abundance. At the time, photographs were considered at least as important as the content of the story—if not more important than the stories to which they were attached. This philosophy would later influence and shape other publications such as LIFE magazine in the United States. Höch understood the power of the quantity of images and exploited them for their familiarity and impact. She notes, “that the image impact of an article - for example, a gentleman’s collar - could produce a stronger impression if a photograph of one of them were taken, cut out, and ten such cut-out collars were just laid on a table and a photograph made of them.”4 Repetition and unique arrangements drew the eye and the attention of both readers of magazines and patrons of art galleries. BIZ was a consistent source of photographic material for Hannah Höch’s photomontage, most likely because her employment at Ullstein Verlag made it easy for her to obtain copies of the company’s publications. There were three major types of photographs that Höch sampled from this publication: candid political photographs, ethnographic photo-reportage, and advertisements.

The power and influence of Ullstein Verlag was buoyed by the many smaller and more specialized news magazines that it published alongside BIZ. Die Dame (The Lady) sought to create a market for the working Weimar woman, who made up around 35 percent of the working population by 1925.5 The articles and advertisements of Die Dame frequently featured idealized photographs of the New Woman, especially bourgeois iterations of this idealized type. Höch most certainly would have seen these depictions of women in the print media, because Höch worked at Ullstein Verlag shortly after her arrival to Berlin in the late 1910s and worked for Die Dame as a pattern designer for the clothing section of the publication. Höch even used these patterns in her collages in the early 1920s, and some of the patterns might even have been of her own design.

Androgyny, a common identifier of the New Woman, and political satire went hand-in-hand in Höch’s photomontages and play a prominent role in Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser. Within the “Anti-Dada” corner of the photomontage is World War I war hero General Field Marshall Friedrich von Hindenburg, but his head rests upon the body of a modern dancer, identified by Maud Lavin to be Sent M’ahesa.6 Other political figures, such as President Ebert, are also depicted in this way. Ebert is identified by his goatee and his head has been transplanted onto the body of a topless dancer. Höch renders these serious masculine figures of authority and power both silly and using allusion to the New Woman to call their manliness and power into question. The establishment of the Weimar Republic led to a shifting of the German culture to a more liberal one. The shortage of men after the war led to an influx in the number of working women in Germany. Many of these female laborers began wearing more masculine clothes and cutting their hair shorter, creating an androgynous look that became synonymous to the New Woman in Weimar Germany.7 Jula Dech sums up this transition well: “Taboos of sexual deviancy were thrown out with the Wilhelmine corset. Homosexuality, transvestism, and bisexuality were discussed often in the new republic and, at least in the large cities, practiced.”8 Dech also mentions the psychoanalytic notion proposed by Otto Weininger and Magnus Hirschfeld of “das dritte Geschecht” or the third sex.9 This theory of the third sex argued that there was an inherent sexuality that, like the androgynous dress of the New Woman, combined characteristics of both the male and female genders into one body.10 This sexual liberation and experimentation was something that Höch not only commented on in her work, but also in which she participated. She was part of this new movement of female labor as a pattern designer at Ullstein Verlag, she dressed in a more gender-ambiguous manner, and (as mentioned above) she had a romantic relationship with the female Dutch poet, Til Brugman, from 1926 until 1935. For the male politicians, this androgyny most certainly emasculated them, because being associated with the androgynous ideal of the New Woman was probably not something they desired or made them look powerful to the traditional bourgeois. The style that gives power to the Weimar woman takes power away from the men in charge. This photomontage demonstrates well not only how Höch used photomontage and mass culture to criticize society, but also how Höch is actively thinking about the relationship between mass culture and its ideas about women of the Weimar Republic.

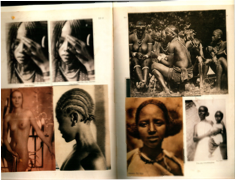

After a period of only a few photomontages depicting women, Hannah Höch began collecting images in 1926 to serve as future source material and inspiration. This Scrapbook (figure 2) is a collection of photographs taken nearly exclusively from Ullstein Verlag publications such as BIZ and Die Dame. She collected the photographs over time, deciding the order and creating the book in 1933 by pasting the photos into an issue of Die Dame.11 The Scrapbook’s themes are pulled from the mass media and suggest, “how Weimar women, particularly those who like Höch considered themselves to be New Women, may have interpreted New Woman stereotypes.”12 Unlike her previous photomontages, all of the images in the Scrapbook exist in their entirety. None of the images are violated or cut; they are arranged neatly side by side without overlapping or obstructing one another.

Figure 2. Pages from Hannah Höch’s Album (Scrapbook), 1933. Scan from Hannah Höch album. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag. 2004. n. pag.

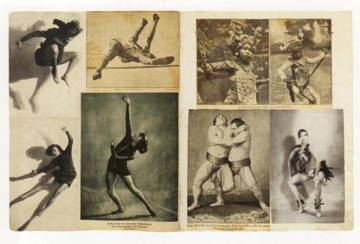

Many pages of the Scrapbook, such as those in figure 3, show how Höch montages images of Western women and women of non-Western cultures explore how print culture treats the idea of the New Woman. As one can see in the facing pages of the Scrapbook in Figure 2, Höch connects images from Ullstein publications from Germany’s former colonies, a common feature of Weimar newsmagazines, to the New Woman. Although not all of the women in these photographs are nude, the nudity of the white woman in the bottom left corner is connected across the page to her African counterparts in the other images. Höch decontextualizes an erotic photograph by juxtaposing it to ethnographic images of nude women. These same associations between Weimar women and foreign subjects are made on other pages that connect more explicitly to images of the New Woman that inhabit Höch’s Dada photomontages such as Schnitt mit Küchenmesser.13 Modern dancers on the left page of figure 3 and a photograph of the burlesque dancer are placed with photos of a Balinese child dancing in a trance and two sumo wrestlers in a pose that resembles a tango. The short hair, the nudity of the burlesque dancer, and the freedom of movement are representations of the New Woman that Höch connects to the non-Western women and ideas of the Scrapbook. By placing these obvious identifiers of the New Woman, the modern dancer with short hair, side-by-side with these exotic photographs, Höch equates her ideas about the New Woman with the otherness of non-Western cultures. Even though it may seems as if women were liberated in the 1920s, Höch shows that she feels the idea of the New Woman is divorced from her actual lived experience as a woman in German society, and that she herself doesn’t feel like a New Woman.

Figure 3. Pages from Hannah Höch’s Album (Scrapbook), 1933. Scan from Hannah Höch album. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag. 2004. n. pag.

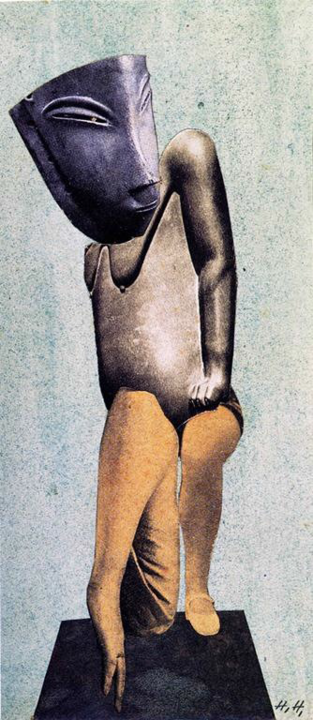

These associations between exotic women and cultures and the New Woman became important in works such as Denkmal I (1924, Figure 4), an early work in the series Aus einem ethnographischen Museum. The standing figure is a photomontage integrating both the ethnographic and the female imagery that might have been found in a publication such as Die Dame. The head and torso appear to be taken from separate African statues and photomontaged together, and the figure has an arm with a balled-up fist that appears to be of an African person of unknown gender. The legs of the figure in Denkmal I are taken from images of Western women - the left a ballerina slipper and the right an inverted arm bent at the elbow. The elbow is the top of the leg with both the forearm and the upper arm extending down. The hand and fingers of the arm extend the furthest down, as if it were a foot extending out in a dance-like pose, connecting it to this repeated trope of the New Woman as a dancer.

Figure 4. Denkmal I: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Memorial I: From an Ethnographic Museum), 1924, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin.

Her choice in ethnographic material and the style in which she frames her works in Aus einem ethnographischen Museum indicate that she was focusing on how the framing of a work contextualizes or changes the context of a work. The bottom of Denkmal I has a black rhombus that appears as if it is a base or a pedestal for the photomontage above it. A framing device such as a pedestal appears in several other members of the Aus einem ethnographischen Museum series. These pedestals create the context for the museum that the title of the series implies, that these works are being exhibited in a pedagogical context for education and instruction, not for religious or social function. Instead, this photomontaged object is placed on a pedestal and treated as a Western object d’art, obstructing or preventing an true understanding of the object. This fragmentation of the context for the work is reflected in the photomontage itself, which combines disparate images to create a new whole. In many cases in Höch’s work, including Denkmal I, the composite of the photomontage is something grotesque and unnatural in appearance. The grotesque object on the pedestal creates a contradiction, “The base, which traditionally presents the wholeness and perfection of an object on display, is used by Höch in these works as a pedestal for her fragmentary, grotesque, and sometimes humorous montages of multicultural fragments.”14 Höch presents a sculpture in this photomontage that is broken and ugly, a critique of her ethnographic and New Woman subject similar to that expressed in the Scrapbook, but not yet an explicit condemnation.

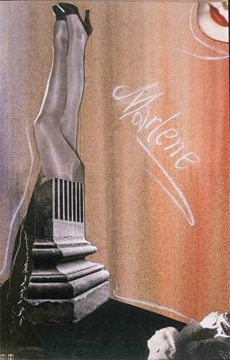

Marlene, 1930 (Figure 5), is an example of the stronger stance Höch takes against Weimar culture by the end of the decade. By combining the base of a column and a pair of bare legs, Höch creates a sexual obelisk, at which the men in the lower right corner stare and cat call under the sun of a smiling woman's face. The presentation of the female figure remains important from Denkmal I. The legs are removed from their original context - the person to whom they belong - and are placed on a pedestal. This juxtaposition of men ogling a pair of legs without a body or a face to accompany allows Höch to reveal the imbalance of male and female representation in the media. Although women gained a larger role in society during the Weimar Republic, Höch remains unsatisfied with the progress of society in which the New Woman is objectified in the sex symbols of the time, such as Marlene Dietrich, a film actress that Höch alludes to here by name.15 The smiling lips in the top right corner appear to smile down approvingly on this scene, perhaps indicating the approval of the media on this type of objectification. The female subjects of Höch’s photomontage work only represented printed representations of women, but with the allusion to Dietrich, Höch’s critique expands to film, the other main engine of Weimar mass culture.

The use of images of the New Woman such as the dancers in Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser, the African and Oceanic photographs that Höch associates with the alienation she feels towards the idea of the New Woman, and their use within the photomontages of the late Weimar Republic indicate an increasing skepticism on Höch’s part to any actual change in women’s roles and freedom in society. Much like the main character of Irmgard Keun’s novel, The Artificial Silk Girl, Höch realizes that one is more likely to find the New Woman in the pages of Die Dame, on stage at a cabaret, or the film Der blaue Engel than in the actual streets of Berlin.

Figure 5. Marlene, 1930, Dakis Joannou, Athens.

Höch quoted in Taylor, Brandon. Collage: The Making of Modern Art. New York: Thames. 47. (Back)

Makela, Maria. “By Design: The Early Work of Hannah Höch in Context.” The Photomontages of Hannah Höch. Germany: Cantz. 1996. 59. (Back)

Lavin, Maud. Cut with the Kitchen Knife: The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. 51. (Back)

Höch, Hannah. “A Few Words on Photomontage.” Art of the Twentieth Century: A Reader. ed. Jason Gaiger and Paul Wood. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003. 113. Print. (Back)

Lavin, 4 (Back)

Lavin, 19 (Back)

Peukert, Detlev J.K. The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity. New York: Hill & Wang, 1993. 96. (Back)

Dech, Jula. Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands. Berlin: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1989. 62. “Mit dem wilhelminischen Korsett werden auch die Tabus abgeworfen, mit denen sexuelle Abweichungen bis dahin strikt belegt sind. Homosexualität, Transvestitentum, Bisesualität, werden in der neuen Republik relative offen diskutiert und - zumindest in den Metropolen - auch praktiziert.” (Back)

Dech, 62 (Back)

Lavin 186 (Back)

Lavin, 73 (Back)

Lavin, 74 (Back)

Lavin, 75 (Back)

Lavin, 163 (Back)

Lavin, 185 (Back)

Bibliography

Dech, Jula. Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands. Berlin: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1989. 62.

Höch, Hannah. “A Few Words on Photomontage.” Art of the Twentieth Century: A Reader. ed. Jason Gaiger and Paul Wood. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003.

Lavin, Maud. Cut with the Kitchen Knife : The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Makela, Maria. “By Design: The Early Work of Hannah Höch in Context.” The Photomontages of Hannah Höch. Germany: Cantz. 1996.

Peukert, Detlev J.K. The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity. New York: Hill & Wang, 1993.

Taylor, Brandon. Collage: The Making of Modern Art. New York: Thames.

Thomas Baldwin is an editor for Things Created By People and currently has almost no social media presence.