Part 1: A History

It becomes necessary at some point to shed the cumbersome conceptions of pantheons and gods. What pantheons and gods truly represent is a system to describe the natural world. In fact, gods are merely inhabitants of the world as it is. They are not shadows of a higher world any more than reality as humanity perceives it is. There is no play with shadowboxing here, no puppeteers. They are able to tolerate living in the real world.

Here, again, another division in conceptions becomes necessary, namely that between the “real” world that is perceptible to the senses and the extensions of the senses, such as an electron microscope, and the real world, that which evades the senses and the significatory process, the world of interpenetrated opposites, the Dionysian, in Nietzsche’s nomenclature. The world as we perceive it, that is to say, the “real” is determined solely by language. Something that does not have a name cannot exist, and there is a name for everything. Indeed, Heidegger lays this out in Sein und Zeit, chapter 4, when he says that existence is language. The real, that is the Real, the Kantian noumenal, the Dionysian, that which is perpetually out of reach, where language breaks down, this is a world that can only be illuminated by the blackest of lights. Borrowing a turn of phrase from the necromantic revival that accompanied modernism, this latter world will be referred to as the Second World.

Gods and pantheons then are an open acknowledgement of a literally supernatural, extrasensory world, which is shut to humanity.1 This is the world that a necromancer must access in order to gain the wisdom of the world. However, how different are the rituals and magic words that the necromancer must employ in order to access the Second World from the logical tricks and linguistic tongue twisters that a philosopher must perform in order to reach hints of the truth?

Perhaps the most important group in the establishment of the necromantic tradition was the Druids. The Druids were the intellectual class of Celtic society, which, at its height, stretched from Ireland to central Europe and south to the Iberian Peninsula. These people were the barbarians that lived beyond the gates of the poleis about which the Greeks exchanged hushed whispers. Yet the Druids were highly sophisticated. One historian claims that the true nature of the Druids was a mishmash of careers; the Druids were “philosophers, judges, educators, historians, doctors, seers, astronomers, and astrologers.”2 The culture of the Druids survived part and parcel until the beginnings of true Christian dominion over European thought.3

Druids derive their name etymologically from the phrase “dru-wid – oak knowledge.”4 Lactantius in his commentary on Statius, a first century BCE Flavian poet, said that the Druids believed that ritual magic and enlightenment could only occur in oaken groves “dense and ancient, untouched by human hand and impervious to the beams of the sun.”5 The Druids professed a special connection with nature. Nature was something wholly sacrosanct that could not and should not be grasped by humans. Yet they tried to take natural wisdom about the nature of reality from the trees.

It is worth fixating on the belief that the groves in which Druid ritual magic was practiced were “impervious to the beams of the sun.” However, in Druidism, the inky blackness of the forest grove was believed to be the home of wisdom. Freedom from the light deprives the eyes from any stimulus, removing the world of sensory perception from making an appearance. The early Druids did not use a written language, but this does not mean that they were illiterate; they simply refused to write anything down. This is yet another way that they deprived themselves from the pleasantries of the world of appearances (a common Nietzschean refrain). The rituals and ceremonies were totally blacked out; the only interaction was purely human communication with the Second World.

The Druids, in all actuality, would most likely have agreed with Heraclitus. Rivers, in their throbbing perpetual motion, were sacred for the druids, who claimed “that the river’s bank, the brink of the water, was always that place where éicse, wisdom, knowledge and poetry was revealed.” There was always the notion of an unceasing flux. One can easily imagine a Druid priest preparing a sacrifice for Amairgen, god of the ocean and all the waters of the world, who also was said to embody “the primeval unity of all things.”7

But it was most likely due to their status as “barbarians” that the Druids eventually found trouble. Druidism (and all of the movements that came after, many of which, by geographical proximity alone must at least be considered descendants of the original Celtic mythologies) opposed the philosophia of the Greeks, except the pre-Socratics. By their very barbarian nature, the necromancers of the Druids and their posterity opposed and upturned the nature of the Greeks, Heraclitus excluded.

The posterity of the Druids was the pagan tradition. This includes the folk beliefs, traditions, and even the religious aspects of the peoples that populated the “countryside” of Roman and later the Germanic Holy Roman Empire. Importantly, this definition (the correct philological definition, derived from the Latin pagani, referring to the rural and agrarian; a true pagan would be a backwoodsman) excludes the Greco-Roman-Christian tradition, favoring the more-often-than-not Celtic traditions, which would have at least been tinged by Druidism. The pagan traditions, especially the traditions of necromancy, are the inheritors of the barbarian status.

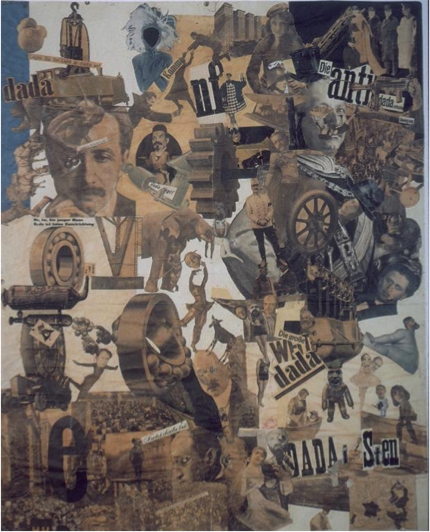

However, during the first millennium of the Common Era, magic experienced a serious split, dividing it irrevocably. Because of the Greco-Roman-Christian intrusions into the pagan world of most of Europe, magic, itself a purely negative phenomenon, as each utterance of a magic word provoked a chasm to split open reality, was subjected to positivism. Primitive forms of the scientific method were foisted upon necromancers, some of whom leapt at the chance to prove that their endangered sector could stand up to so-called scientific scrutiny (which, of course, it could not). Even more so than the primitive scientism, a greater threat to the pagan magic tradition was the appropriation of the Celtic/pagan traditions by the neo-Platonic strains of contemporary Christianity (this can also be associated with Augustinism, so-named after St. Augustine). The schism of the two magics was then between that which had been Greekified and philosophied (mostly astronomy/astrology and some alchemy), hereafter referred to as light magic, and magic that maintained its original barbarian character, which was given the name Nigromantie, punning with nekros and negros, which is now in the parlance of today referred to as necromancy or “black” magic.

Most of the “magical” disciplines existed prior as a quasi-science. Of particular interest is the notion of committing “experiments” through fiction and lying, instead of through any sort of positivistic scientific method. As Paolo Zambelli said of magical texts, “they were often falsified.”8 In other words, by their very nature, they were fictional and adhered to a different mode of writing than the “logical” scientific writings of the Greeks. Black magic was a “negative science,” to borrow slightly from Theodor Adorno, freeing itself from the tyranny of the burden of proof. Light magic, however, found itself tested into extinction; once subjected to Greek rigor, it became a byword for a joke, nonsense, or poppycock. Contemporary light magic is something practiced on the boardwalks of the world, with every two-bit shyster willing to read a palm for a few dollars or tell the future based on one’s horoscope. As light magicians began to use statistics and apply a primitive scientific method to their work, their position became untenable. Any magic that lays claim to being based in logico-positivism simply cannot be magic at all. One could not be a magician and a scientist. True magic, therefore, must be black magic.

Pope John XXII, the second pope of the Avignon Papacy, did not recognize this, however. This pope began to see sovereignty struggles in terms of metaphysical issues and he issued a series of bulls condemning policies that he viewed would weaken his material power. As Isabel Iribarren noted, “Pope John XXII launched a doctrinal enterprise of some import: the assimilation of practices of black magic into the crime of heresy.”9 Of the bulls, the Spondet quas non exhibitent was perhaps the most important in the condemnation of black magic. Only light magic was allowed to continue. Any form of necromancy or communication with the dead was lumped with witchcraft, which of course the Bible handles with the famous quotation, “Never suffer a witch to live” (Ex. 22:18, King James version).

Part 2: Reading with Nietzsche

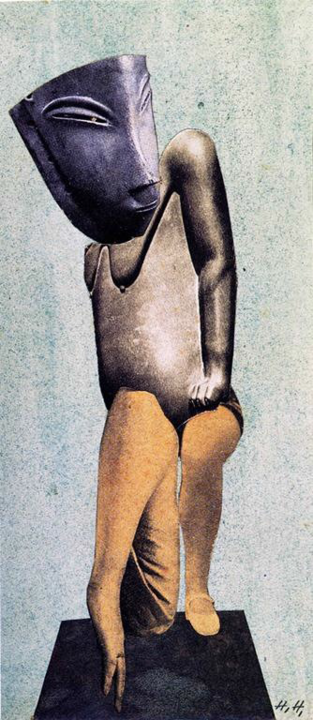

“Whatever is profound loves masks… Every profound spirit needs a mask.”11 With these words, the door to necromancy is opened. Necromancy is not a despectralizing process, but rather spectralizing itself, or, more accurately, respectralizing.

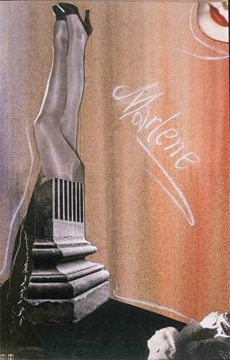

Despectralization involves making something palatable and understandable, indeed classifiable. Is this not the process of naming that the human race employs? We find ourselves startled by the Second World. But by classifying the world, the specters are lost. These specters are things that defy the law of opposites; they originate from behind the genealogy of morality and languages (if those two could ever be separated). The profound spirits are in need of a mask, for otherwise the entire society of the human race would collapse. Who masks, though? No one other than the positivists. Haunting, then, is the re-intrusion of the originary meaning of these profound spirits, who chafe at the edge of their names.

Respectralizing, through the process of necromancy, is nothing more than de-masking what could barely be masked in the first place. There is a certain sense to holding rituals in the deepest groves of the forest. The first step to employing the negative science of necromancy is blindness, uninterrupted by a world of forms and appearances. This is an overcoming of traditional morality, an assent to the inherent phantasmagorical role of everything that can be perceived when captured in a moment of intoxication or ecstasy. Without sight, a necromancer does not see a sparrow fluttering in the wind or the flag of some soon-extinct nation state filled as though a sail, he feels the wind against his face and is immediately raised aloft as though he himself were the sparrow.

This is the ecstasy of assent to the Second World. “In this case, intoxication has done with reality to such a degree that in the consciousness of the lover12 the cause of it is extinguished and something else seems to have taken its place – a vibration and glittering of all the magic mirrors of Circe.”13 Intoxication is not necessarily brought about through the ingestion of rogue chemicals or drink or sex, but the radical yes that motivates those indulgences, a willingness to see perception bent. This is the role of the necromancer.

The necromancer defeats death, but he also defeats life. He unmasks the delusion of thought that inspires us to name the continual process of life-death-redispersal. Through the radical yes that motivates his experiments (Versuche) in the negative science, he/she is unafraid to commune with the specters beyond life and death; specters that are “irreducible to classical ontology.”14 Derrida mentions that these specters cannot not spook, that we must always be spooked by them. However, this hinges on the holding onto of modes of classical ontologies. The role of the necromancer and of the negative science itself is to oppose the high priest and positive science, locked in dialectic.

Nachwort:

The Versucher, necromancer, philosopher of the future must not be afraid of specters and must attempt (as is the very nature of he or her) to respectralize. This is what Nietzsche was hinting at in his works, especially in The Gay Science, the source of his doctrine of the radical assent, namely Nietzsche’s Epicureanism. A hauntological utopia, like all utopias, remains impossible, and indeed is itself haunting. Nevertheless, it would be helpful to continue along the lines of this thought experiment, including the works of Aleister Crowley, especially his works on the grimoire The Lesser Key of Solomon, detailing the various methods by which many spirits, almost all of them able to undergo multiple readings on multiple valences, can be conjured by a gifted enough necromancer. Are these rituals able to be read as poetry is? And what does that say about poetry? These are both questions that must be dealt with at a later date.