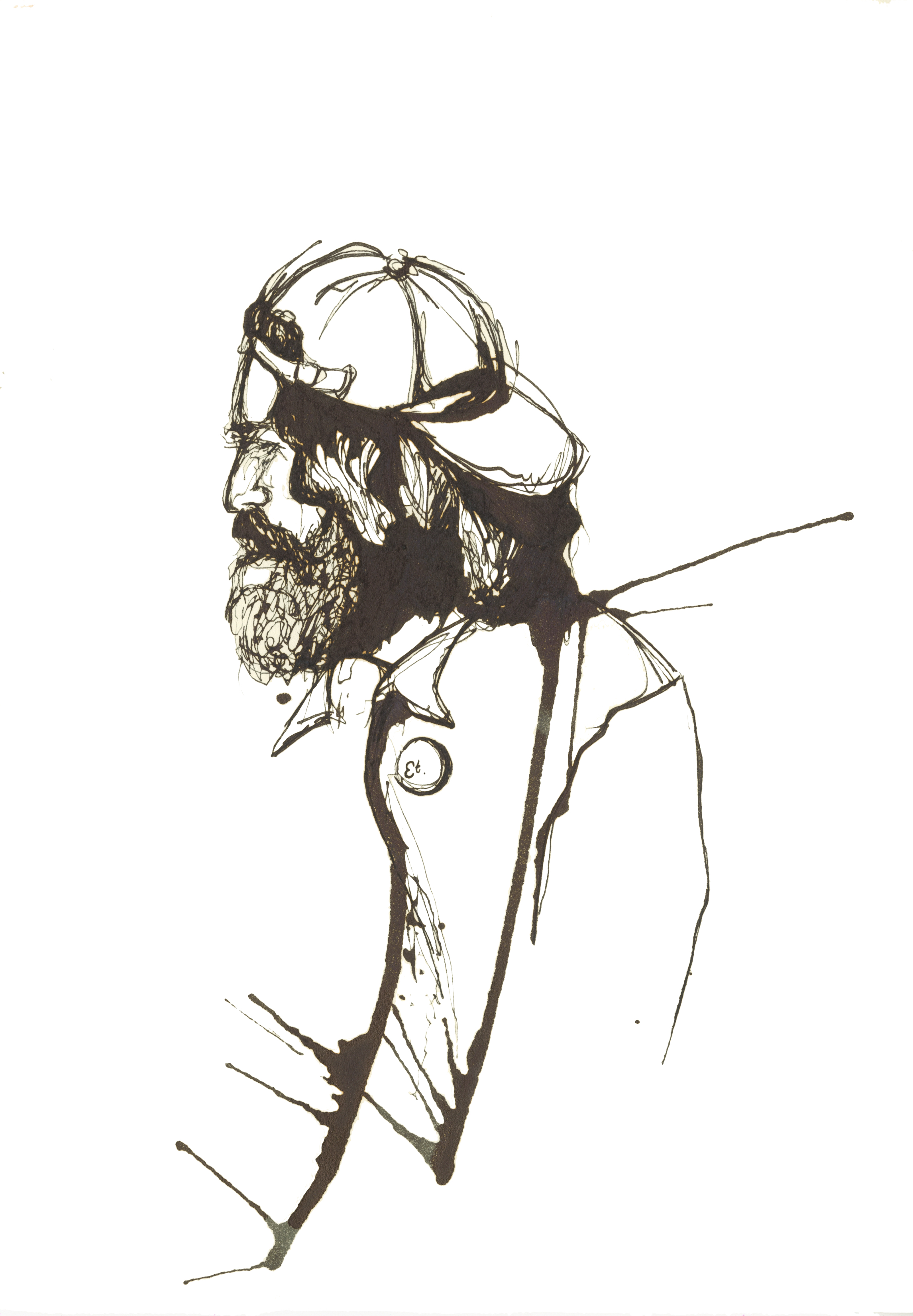

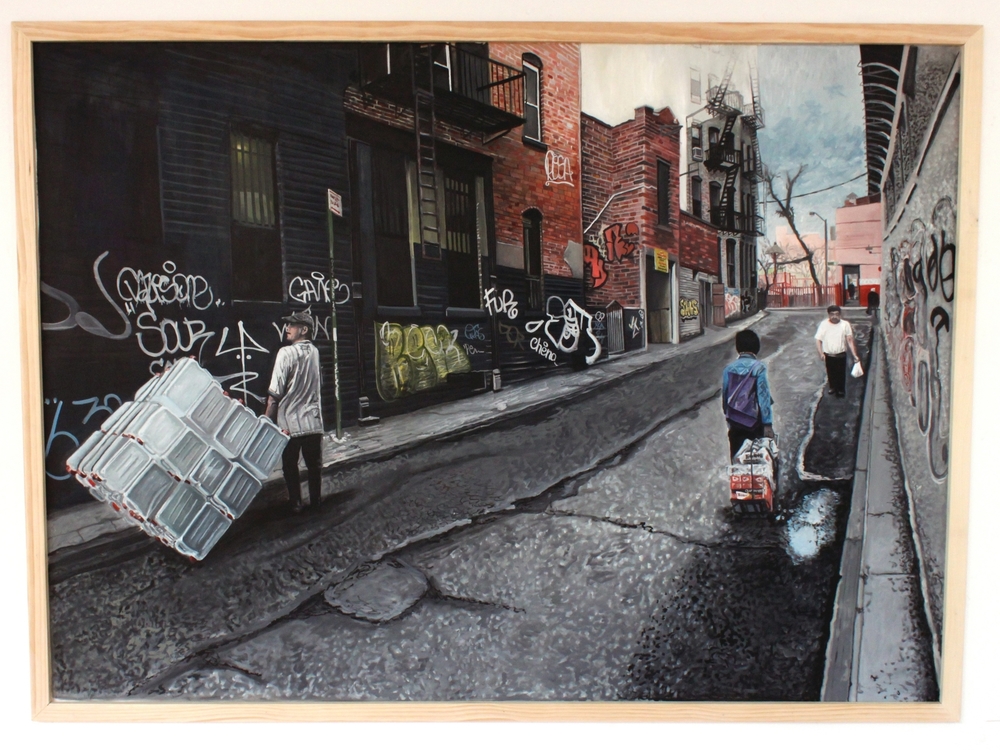

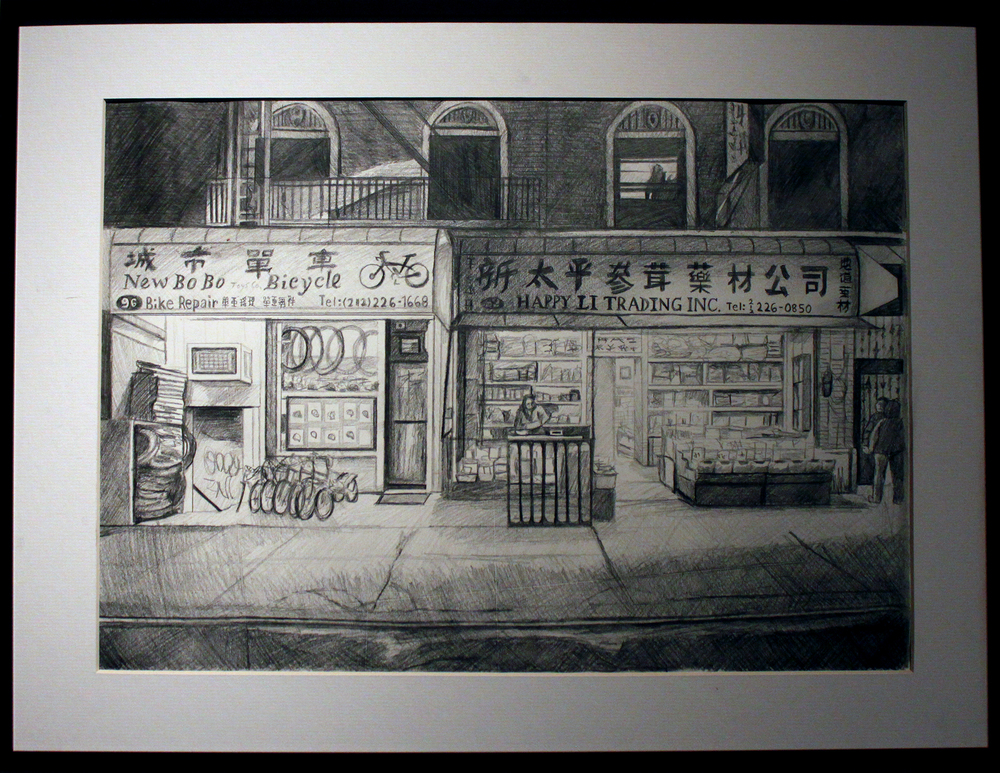

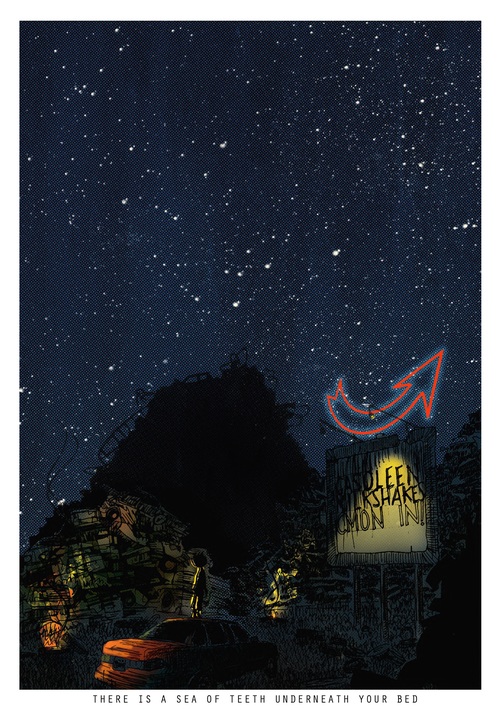

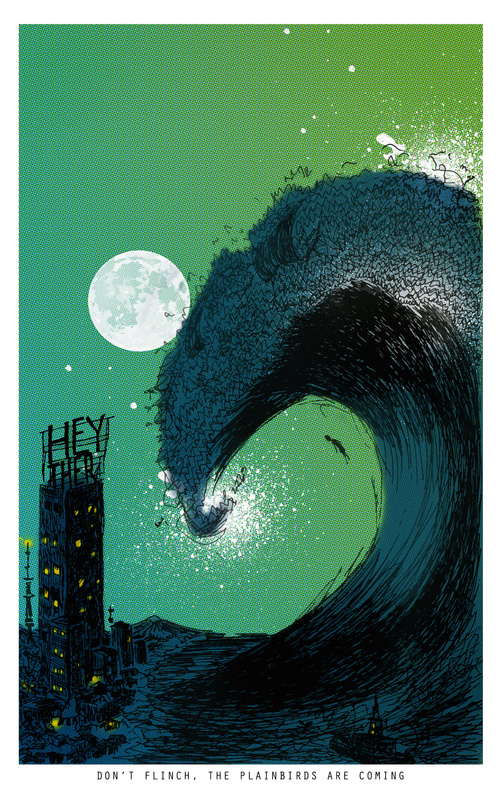

Continuity I, 2017

Artist and illustrator Emily Tat moved to New York with her partner this past fall. Her style incorporates ink drawing and watercolor, sometimes tracing her figures in water and allowing the ink to seep into the damp paper. Ralph Steadman is an easy comparison, and one that she invites. “It’s such a compliment because he is fucking amazing. He uses protractors to make these very straight lines and protractors to draw the eyes. But all around the figures is just ink everywhere.”

Her current style is a recent development in her artistic career. “I used to do photorealistic oil paintings. When I was doing my degree in my final painting course, I had a very specific style, and I felt that I had to stick to it. I got criticized very badly by the professors. So I decided to go another way and began making video art, but I never felt quite into what I was doing. Shortly after I started dating my partner, Guido, we were in his dorm room, he was playing music and I felt like drawing. He only had this calligraphy pen that I still use. It forced me to draw loosely in a way that I never had to before. My favorite thing about drawing this way is that I feel that I can be very abstract and mess around with overlapping colors and spilling ink. I also like it to be very clean, with lots of negative space around what I’m drawing. I never sketch things out, so sometimes I run into the edge of pages.”

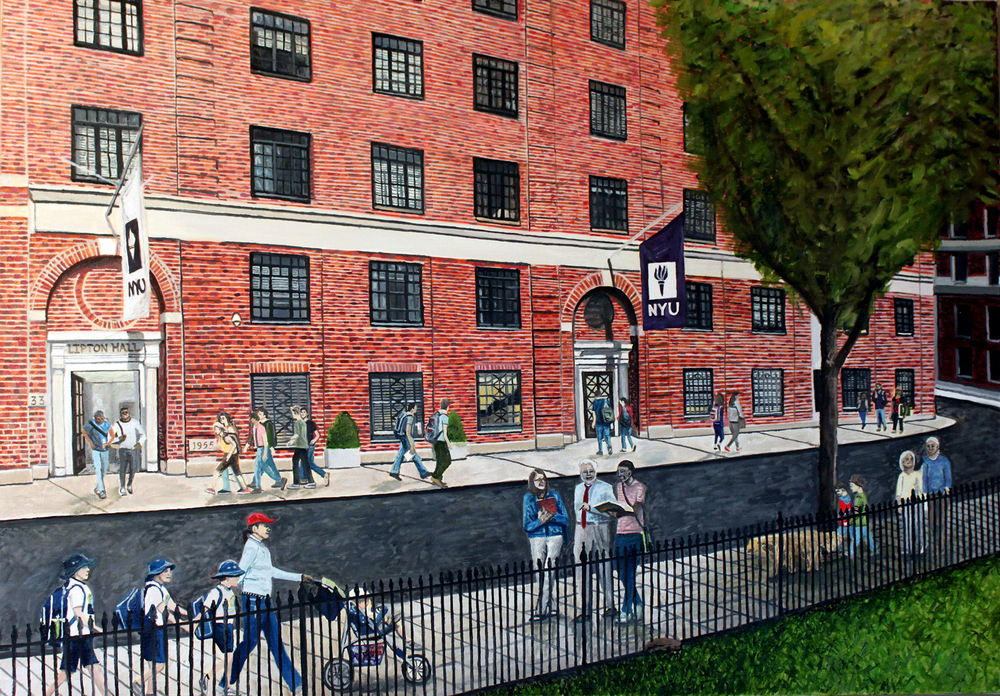

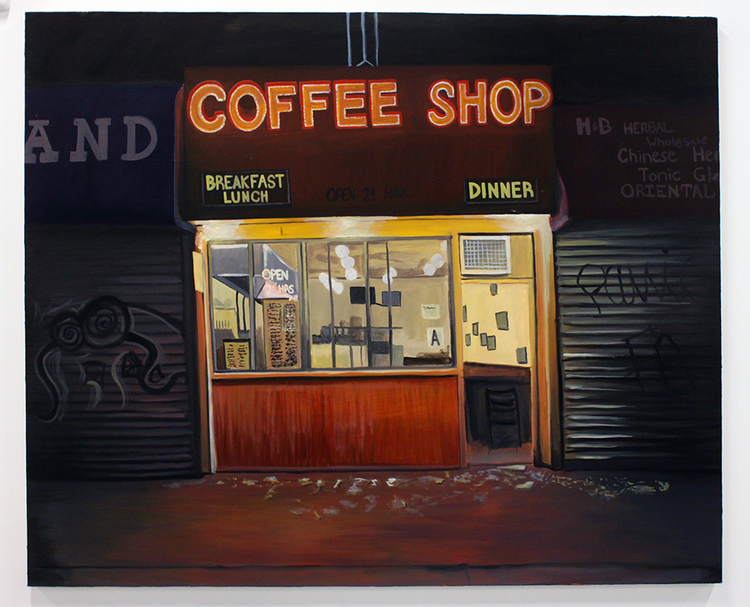

Guido, 2015

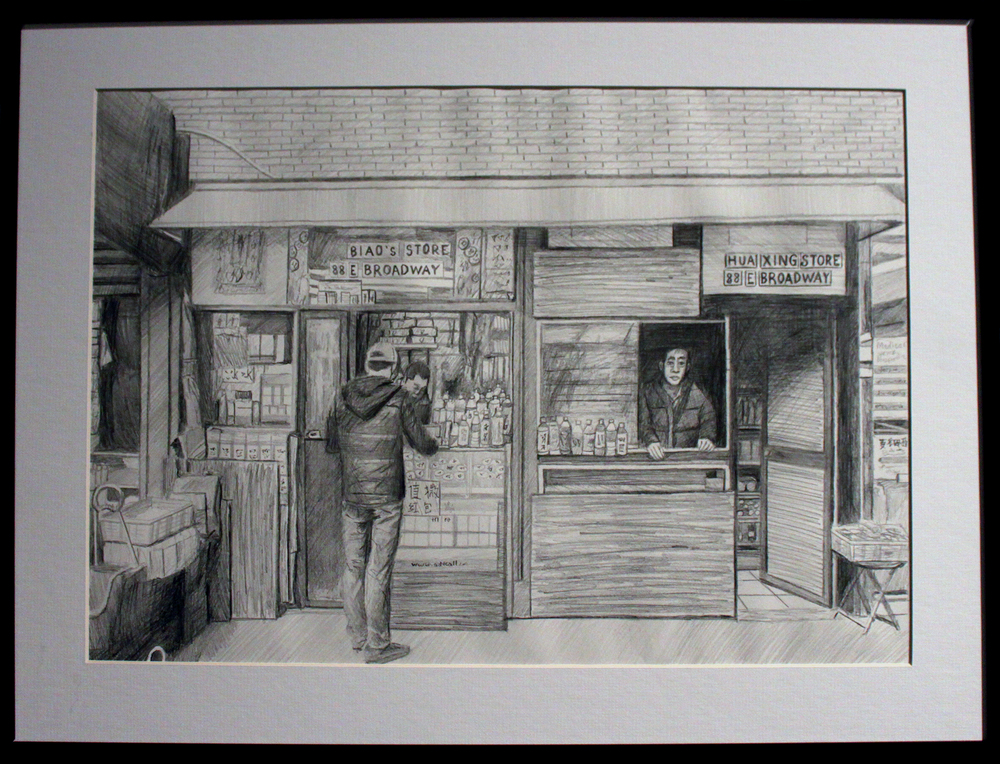

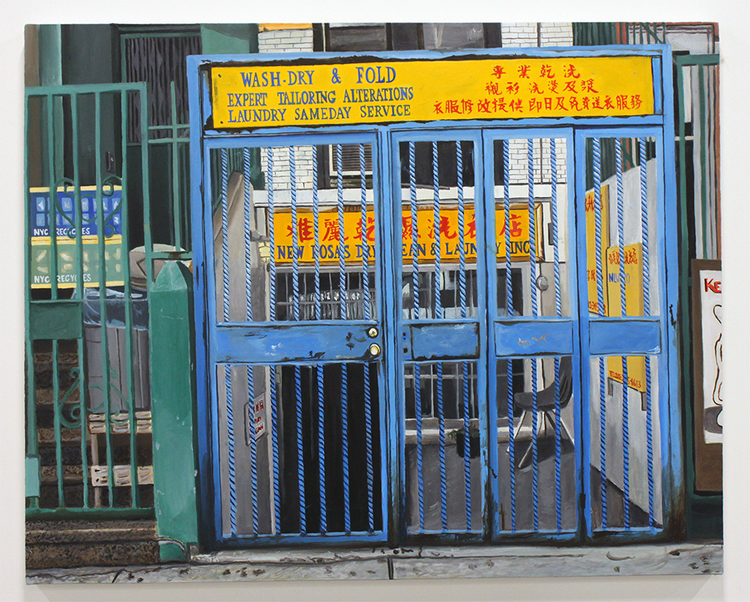

Portraiture is an incredibly important aspect of Emily’s oeuvre, and she strives to capture her sitter’s essence while keeping the form minimal and legible. “I think it’s important to get the form of something, and to keep its structure. At the same time I like to add these weird, abstract elements to it. I do it a lot with feet and hands, and to exaggerate limbs and fingers. It’s important to capture the structure of someone’s face. I was doing a commission for this couple, and they said they really felt that I captured both of them and their connection to each other. That is the depth that is important for me to capture in a drawing… What I’m driving for is for them to see the portrait and say ‘that’s me!’ I get frustrated with myself very quickly. If I feel that I haven’t captured someone it, then it really upsets me.”

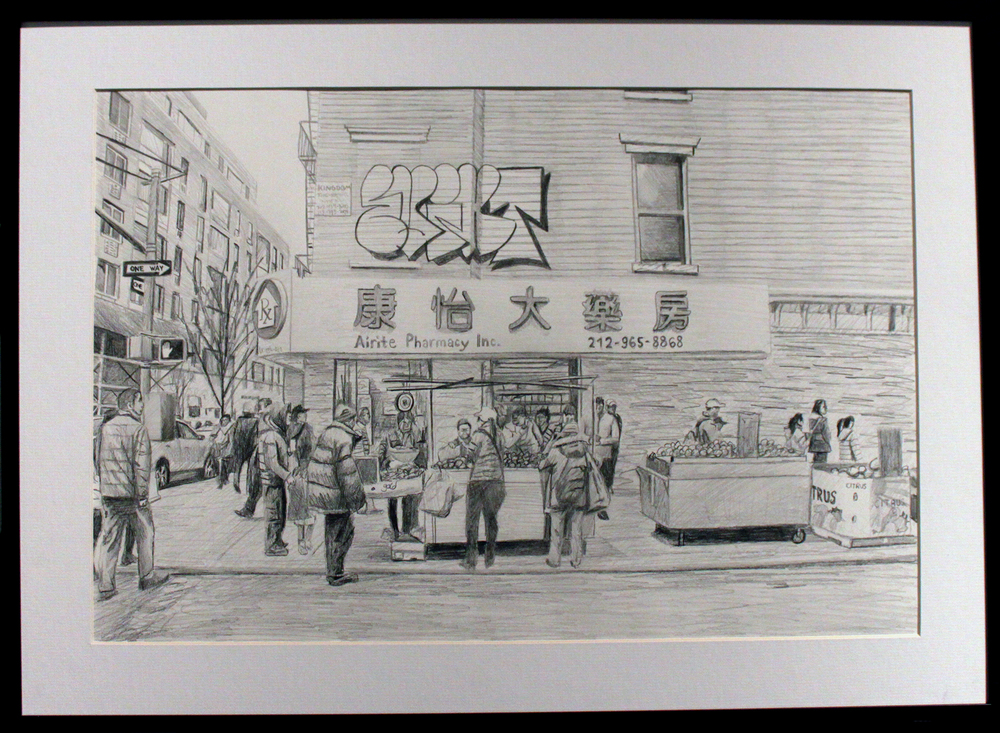

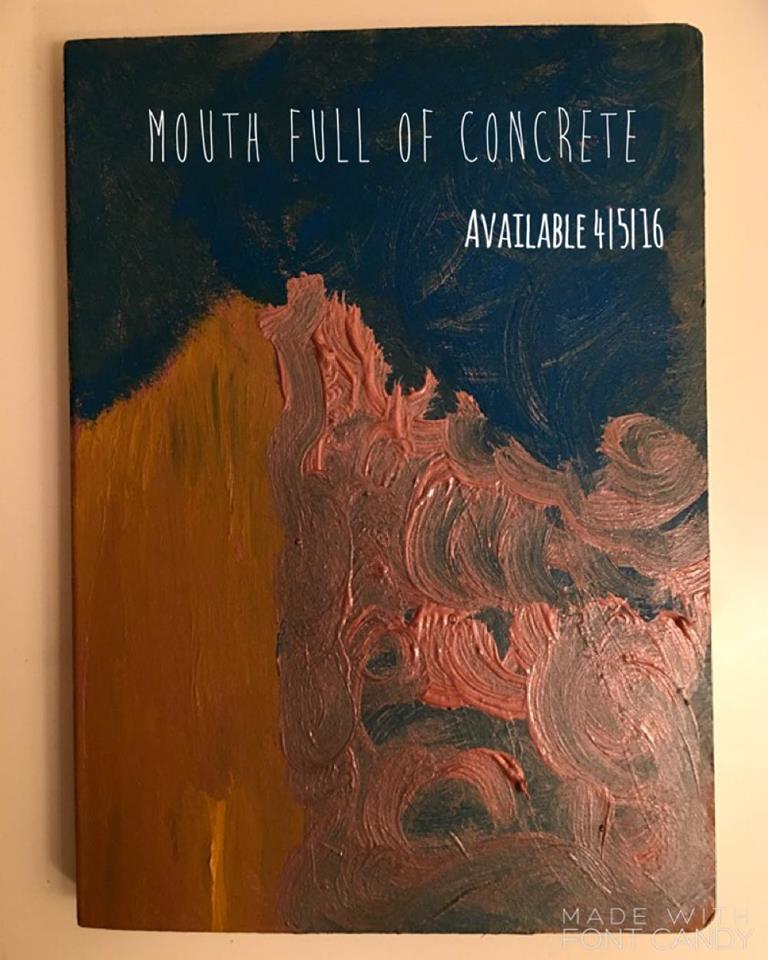

Galentines Day, 2018

What captivates Emily most when portraying subjects are sharp and angular features, but capturing these characteristics is not her main goal. The ritual and process of portraiture is what attracts her to that type of work. “When I first started doing this kind of work, a lot of people asked to pose for me. It’s just really nice when someone wants that moment. If you think about it, unless you’re in a relationship with someone how often do you get to look at someone’s face? You forget things like what color someone’s eyes are or the shape of their nose. You only get to know that when you look at someone’s face over time. So it’s really nice to have that 3 or 4-hour period where I can take a friend, or someone I don’t even know at all, and really look at them. It can make someone very vulnerable if they are posing naked. People often do it when they want a bit of validation or a little moment for themselves. I think people often don’t get enough attention, and so it’s really nice to have the opportunity to give people that recognition.”

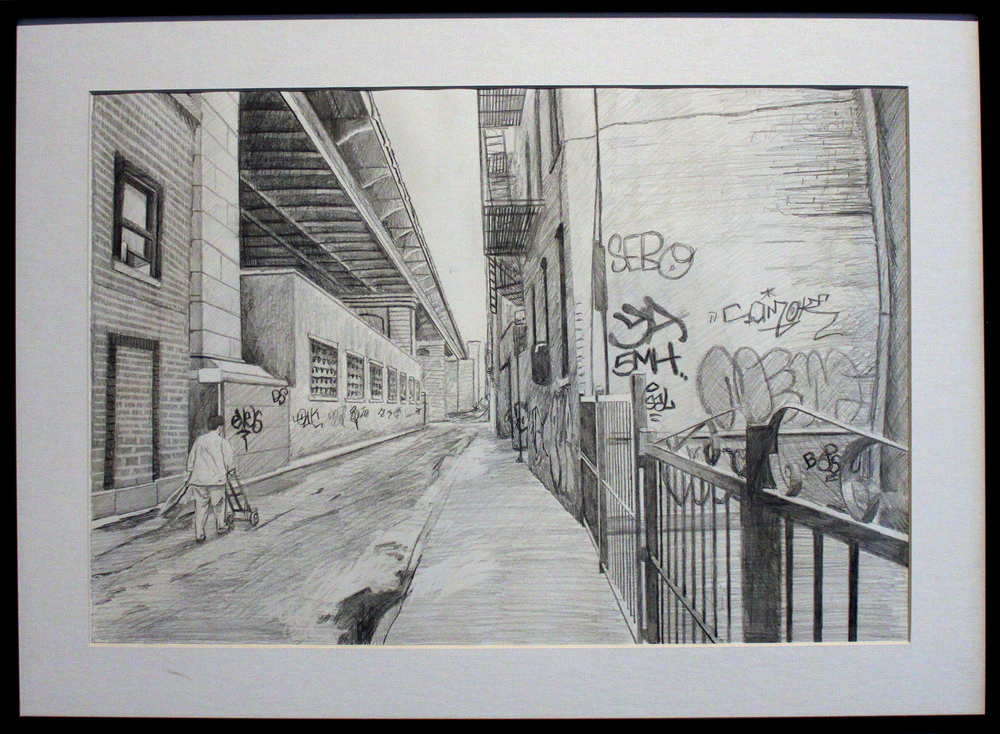

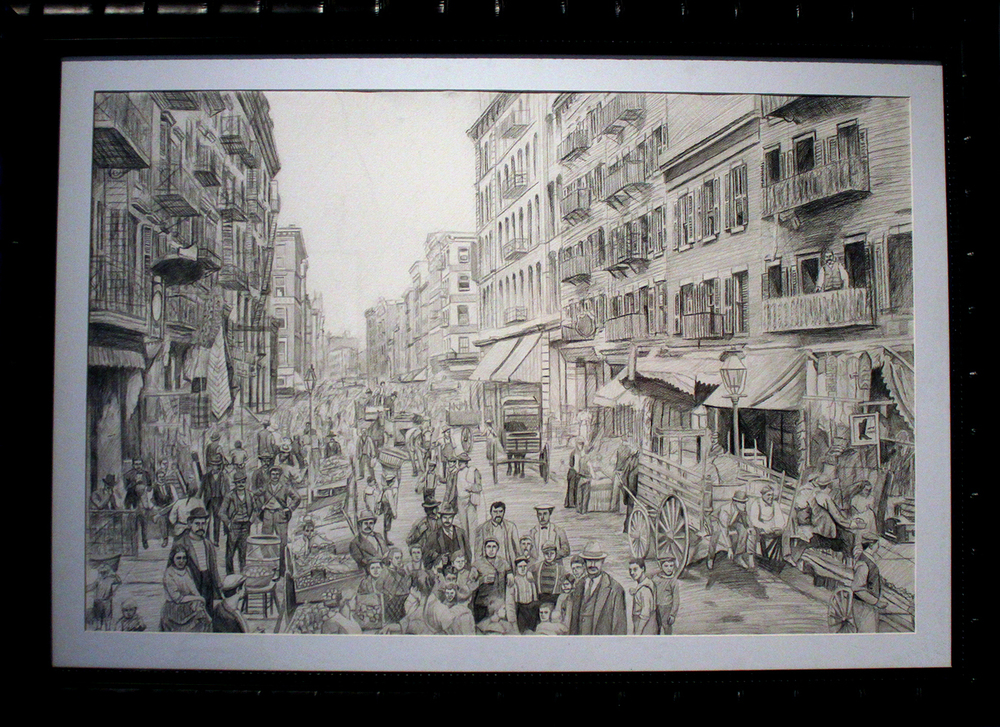

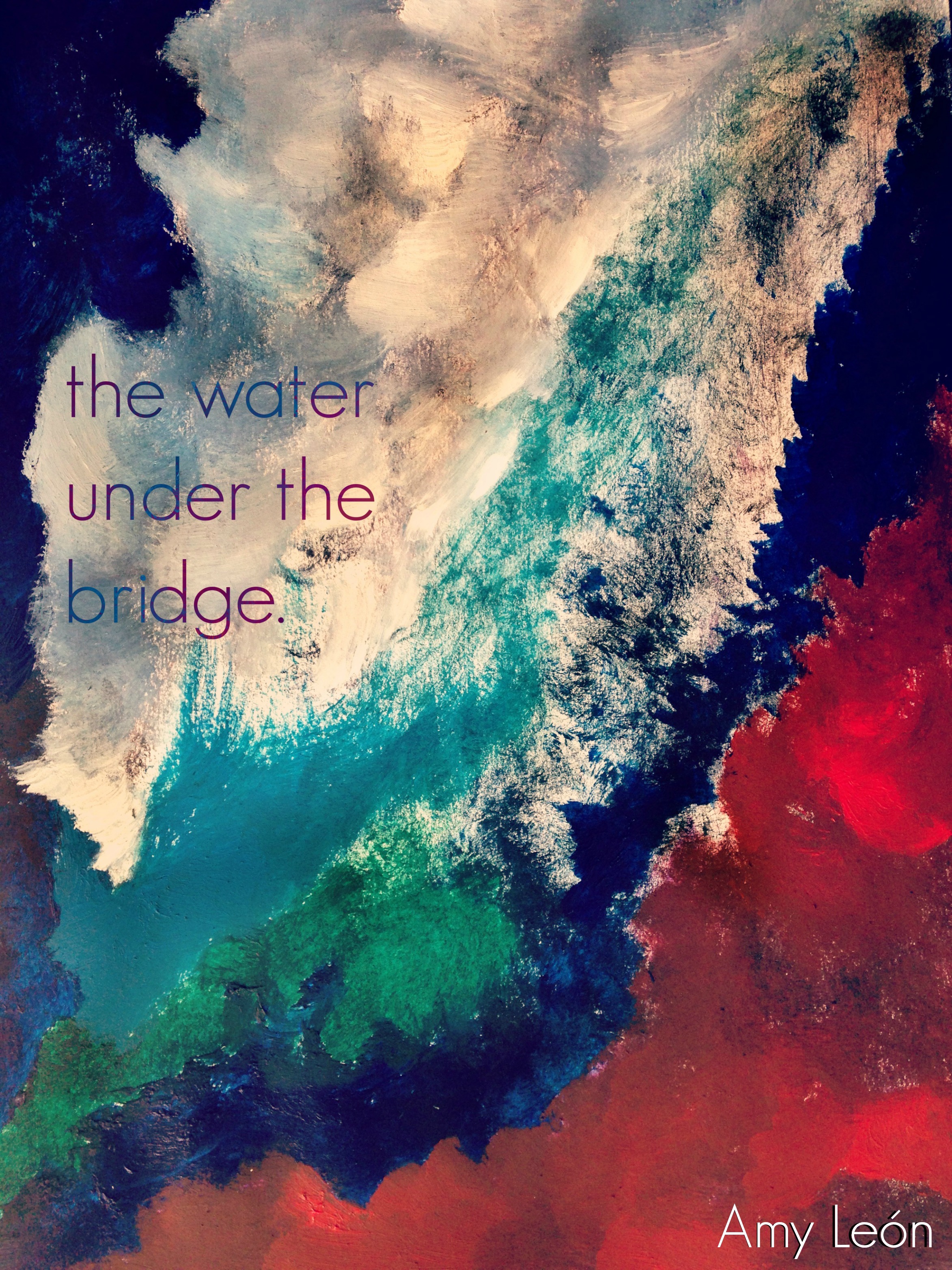

“Since I’ve moved here I’ve had some ups and downs, but I feel as if I am having resurgence” Emily said. She started making single-line drawings, creating still lifes and portraits without lifting her pen from the paper. “I really love it because everything that is in my head can just spill out onto the page. It’s very reflective of the medium that I use as well, because ink is very quick and you have to make decisions immediately.” Her subjects have also become more personal since starting these single-line drawings. Emily showed me a drawing of her and her friend Julia and a drawing of a jar of nutmeg. “[Julia] is just one of my most special friends in the whole entire world. Ever since we met, we have had this incredible friendship that’s never faltered. I don’t have that many friendships like that. Doing a portrait in this way is really reflective of how I feel about her. I enjoyed making single-line drawings of things that comforted me, since I had just moved here. Even though things are different and weird in this country, these drawings remind me of the things in my life that are continuous. It goes beyond relationships between me and other people. There are ones of certain foods that are special to me, because my homesickness manifests itself often through food. Guido and I have this jar of whole nutmeg in our kitchen. Back in London he kept banging on about how he wanted whole nutmeg in the kitchen and he couldn’t find it anywhere, so I found some for him we I went to the south of France. It’s this continuity from our kitchen in London to our kitchen here that mirrors the continuity of our relationship.”

Nutmeg, 2017

You can see more work by Emily Tat on her website.