For many artists on their singular path, often there comes a breaking point. They can continue down the river they’re on, or jump ship and pursue something new. A bit rarer, though, and entirely more enthralling to watch, is the artist that pivots what they’ve been working on into something grander, building upon their strengths and weaknesses and veering right into new territory.

Meet Tristan Carter-Jones.

Emerging on the scene as a rock-soul singer with bedroom-pop sensibilities, Tristan released The Jones EP in November 2014. Boasting the sound of FKA Twigs and Brittany Howards’ lovechild, Carter-Jones was headed down the path of a Brooklyn solo act, hand-picking producers with whom to work. “The Jones EP was kind of fucking dark,” Tristan laughs, “The songs demanded a strange sort of isolation – the sort of spiral that happens when you spend too much time alone in your head.”

This assessment holds water. In the video to Jones EP centerpiece “Bare to Beat,” Tristan loops videos of her own performance of the song, just as she loops her vocals in the most glorious ‘round you’ve heard since counting to three before jumping in on “Row Row Row Your Boat” in Sunday School. From the strikingly personal songwriting to the production credits, she was an artist fully in control of the journey she intended you to go on – a selfish (but rightfully and intriguingly so) representation of the intricacies of her lovelorn psyche. “I was the kid in class who did every part of the group project because I didn’t trust people. I tend to have a very specific vision, and want things exactly as I want them.”

Which is why her 2016 re-emergence – as front woman to an otherwise all-male, all straight, all-white rock band Dakota Jones – couldn’t be more surprising. If you can’t take my word for it, consider that prominent indie blog Obscure Sound wasted no time making their critical imprint on this moment. “The multi-vocal layering [exemplifies] this group’s impressive grasp on both garage-rock and contemporary blues-rock,” they wrote the day of the release. And there it is – the sound we grew to love in 2014, yet pivoted into the world of rock.

“Working with Tim, Scott, and Steve has helped me let go of my obsessiveness,” Tristan explains when I bring up the newfound requirements of fronting a band – namely, working with other people. “They’ve helped me learn that collaboration is actually a lot more fun. It’s the most important part to me now. The most beautiful things come out of that place where I let go and someone else steps in.”

At this point, I’m skeptical of just how much Tristan’s enjoying letting loose of the reigns, but the fact that it’s happening is indisputable. The collaborative nature of Pt. 1 (out now on Bandcamp and Soundcloud) is evident in the first 20 seconds. Gone are the freeform improvisational meditations on family and addiction from The Jones EP (“Different Things”) and the epic pop soundscapes big enough to overwhelm your senses with masterful grandiosity (“Bare to Beat”). Each song on Pt. 1 is as tightly structured and classically produced as The Jones EP highlight (and closer) “Busy Puts.” The players alongside Tristan – Tim Greene, Scott Kramp, and Steve Ross – mix with her voice effortlessly – each piece essential, yet not a single sound extra. It sounds immediately classic. It’s where it’s supposed to be, and a listener can’t help but feel they are too when listening to it. Whereas you can feel the curtains of The Jones EP closing over the windows in the room she’s making it, Pt. 1 sounds like they recorded near a Central Park playground, on a sunny day in the middle of Spring.

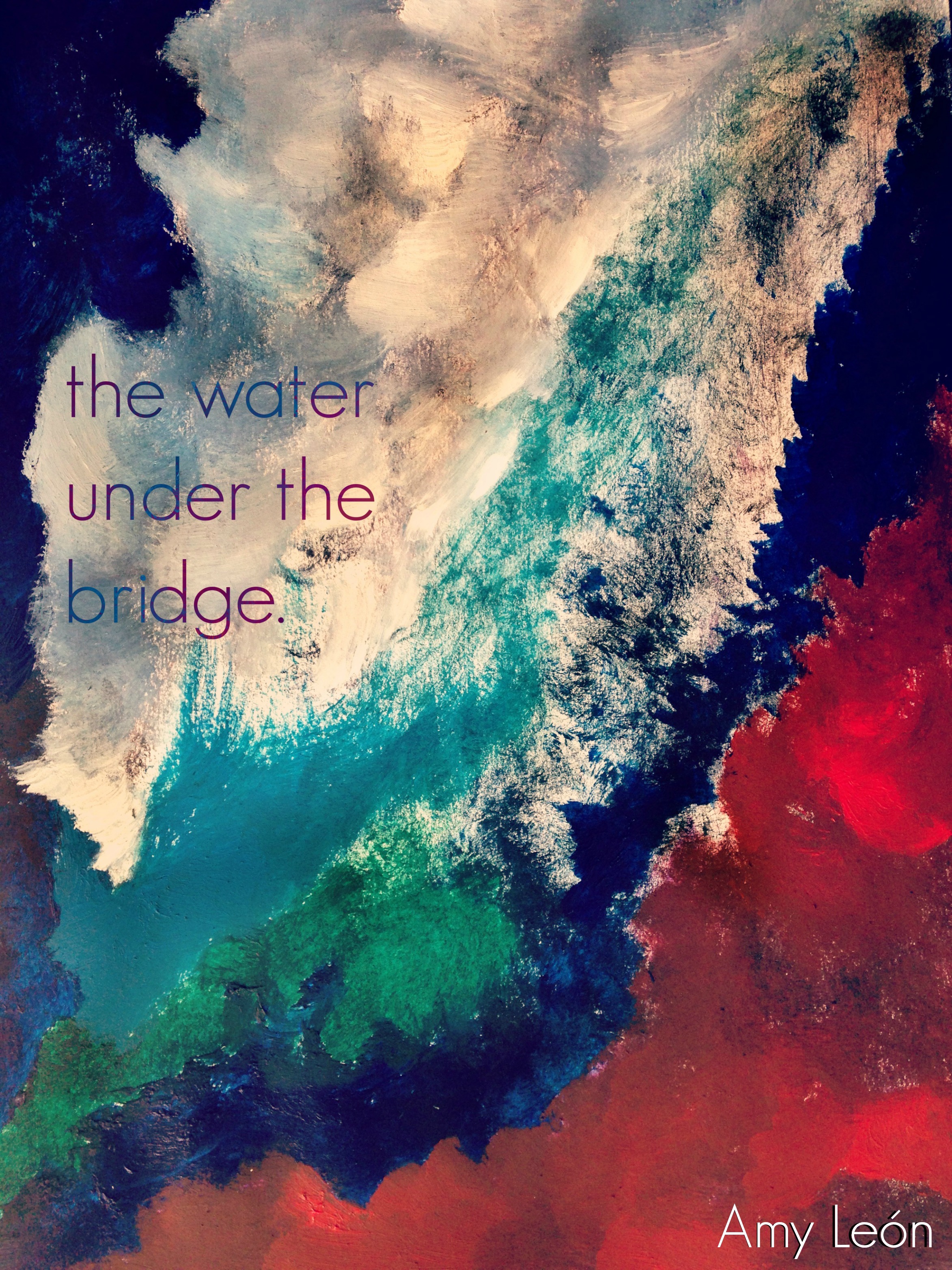

Despite the new sound, Tristan (who still writes each song) insists she’s exploring similar grounds of heartbreak. When asked about the EP’s visceral cover image – a set of white hands choking her – she explains: “Being in love was all I ever wanted. Then I got it and it terrified me to no end. At first I couldn’t eat or sleep and I literally felt a tightening in my chest that was constant. The choking imagery made too much sense to me. White hands around my throat.”

The newfound knowledge on this aspect of life seems to have given Carter-Jones a new source of power. Perhaps the power of setting free a broken heart just to get it broken again, this time wiser and ready for the fight. The power of accepting oneself a little bit more fully at 25 than at 23. “I’m a queer black woman in full control of the music, lyrically, and fronting three straight white men, which is only hilarious to me when I think about it.” She continues, acknowledging the coolness in this, “This is just some of the regular shit that women think about! I’m not special because I’m thinking about BDSM and fucking women. I just don’t think we get the pleasure of hearing these things from a woman’s mouth as often as we should.” She laughs, and suddenly I’m much less skeptical that she’s enjoying this collaborative ride.

Dakota Jones performed their New York debut at The Delancey on October 12th. The show was met with an ecstatic crowd and a confident debut from the band, including tight playing and Tristan’s assured vocals. One of the best aspects of a band is that each member has something at stake. I can’t help wonder if the newfound lightness in spirit and tightness in composition derives from working with individuals who feel excited, and perhaps even lucky, to be the ones providing glorious and classic soundscapes to her glorious voice and classic songwriting.

“I’m a bit gentler with myself now. On my thoughts and on my heart. I’m deeply grateful for the perspective I have now. And for the hope I have now, and for the want to be here that I have now. I never thought I’d be so fucking hopeful. I’m thankful for the patience and great love of the people around me.” She pauses, as if all is finally calm before adding, “And I’m still thankful for my strange-ass mind!”